PARIS NATIVE JAY WELLS RETURNS TO NEW YORK FOR RANGERS CELEBRATION

From pond hockey to the Stanley Cup finals: memories and lessons 25 years on

From pond hockey to the Stanley Cup finals: memories and lessons 25 years on

For News Tips & Advertising call...

Kitchener East - 519-578-8228

Kitchener West - 519-394-0335

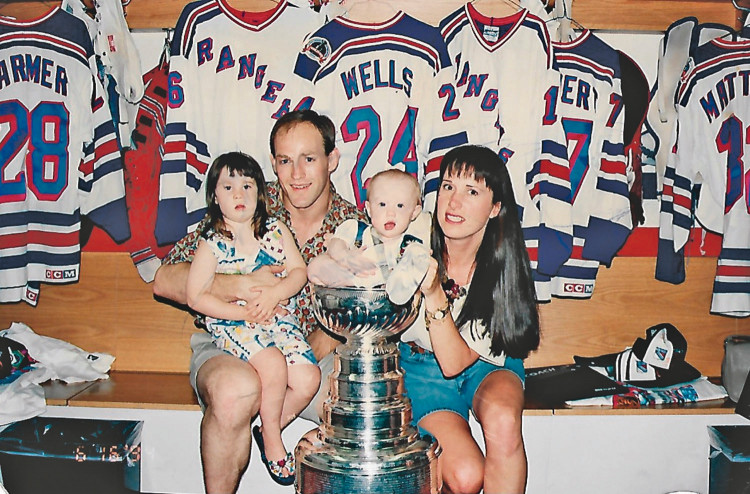

New York Rangers Stanley Cup winner Jay Wells with his family in 1994 with the Stanley Cup. From left: Stephanie, Jay, Alexa, and Colleen. Another daughter, Kendra, was born in 1996.

Photo courtesy of the Wells family.

Photo courtesy of the Wells family.

Jay Wells (front row, right end #24) participates in a ceremony in New York on February 8 commemorating the 1994 New York Rangers team that won the Stanley Cup. The Paris native played defence for the team. Team captain Mark Messier can be seen at the left end of the front row.

By Justin Mowat

Kitchener Citizen

February 13, 2019

Jay Wells and his brother, Bill, came very close to shutting down an entire border crossing between the U.S. and Canada in the summer of 1994.

“Do you have anything to declare?” A Canadian customs officer asked Bill, through the rolled down window of their car.

“Well, if the Stanley Cup is something we have to declare, then yes, we have the cup in the backseat,” he replied.

The officer instructed them to promptly pull over and remove their precious cargo for inspection.

Four out of five of the customs booths on the Lewiston-Queenston Bridge suddenly closed, and all but one of the border guards had vanished from their posts.

“The cars were all honking and they all had to get into one line … and the customs officers, all they wanted to do was get their photo with the Stanley Cup,” Jay said.

“I feel bad for the one guy who had to stay.”

Now, for the 25th anniversary of his Stanley Cup win with the New York Rangers, Jay and his family travelled south February 8 to reunite with his old teammates.

Before leaving, Jay said he was looking forward to reminiscing with the old gang, and sharing the celebration with his wife Colleen and three daughters.

“It’ll be a good opportunity for them to get a taste of what life was like back in my glory days,” Jay said.

But he remembers two incidents in his childhood that could have kept him from getting on the ice at all.

At age one, he was scalded with hot water and lost a large section of skin, and a year later he broke his arm and multiple ribs after getting caught in a tractor’s power take-off shaft.

Luckily, his recovery was swift and he was eventually able to lace up his skates, pick up a stick, and join his older siblings on the frozen pond behind their farmhouse west of Paris.

“I learned an awful lot from my older brothers. I would try to do things that I saw them do and that helped me to develop into the player that I became,” Jay said.

The NHL first recruited Jay’s older brother, Bill, to train and play for the Montreal Canadiens.

He trained with Montreal for two years, but never made it onto the team’s official roster, eventually being sent home.

“If I went to the Montreal Canadiens — with how strong they were back in the ‘70s — I probably would’ve never made the NHL,” Jay said.

The Los Angeles Kings, an up-and-coming team at the time, drafted Jay when he least expected it.

He never intended to play professionally.

And after he’d honed his skills on the ice with the Kings, he eventually found himself signed to the New York Rangers alongside an all star team.

Be that as it may, the good news came with a catch, or rather, a curse.

There was an entrenched rivalry between the Rangers and the New York Americans, who played in the NHL between 1925 and ’42. Both teams called Madison Square Garden their home rink, but their landlord also owned the Rangers.

Many theories have circulated about the cause of the Curse of 1940, also known as Dutton’s Curse, including one Jay remembers being told before a game against the New York Islanders.

Legend has it that after the Rangers won the Stanley Cup in 1940, high on their victory, they forced the Americans team out of the arena they shared, bluntly gesturing to “find somewhere else to play,” Jay explained.

The owner of the evicted team, coach Red Dutton, placed the long-lasting curse on the Rangers, stating they would never win a Stanley Cup ever again.

New York Islanders fans would ominously chant “1940” repeatedly against Jay and the Rangers whenever the teams met for a game.

The curse was finally lifted in the first round of the playoffs that would lead to the Rangers’ ultimate success in 1994.

Mark Messier, a five-time Stanley Cup champion who played alongside Jay, gave the Rangers a succinct piece of advice for winning the trophy: “If you can’t see it, you’ll never seize it.”

There was certainly a lot of pressure on them to win from their defiant coach, Mike Keenan, who only stayed with the team for one year and departed after their victory.

Keenan was a motivator with an attribute that was unique, Jay said.

“He knew how far he could push a person to get the most out of them,” he said.

And everyone on the team needed to be pushed, “they couldn’t be complacent,” Jay said.

As the Rangers made their way through the playoffs and into the Stanley Cup Finals, Jay realized playing well wasn’t just about maintaining his talents on the ice.

“As much as it is physical, it’s twice as much mental,” because if you internalize your wins or your losses too much, you can let your guard down, he said.

The Rangers beat the Vancouver Canucks in game seven of the finals, with team captain Messier scoring the game-winning goal.

However, the moment the win fully sank in for Jay was a while after the final game. It hit when he returned home to Paris.

He and his father were drinking coffee after a small family celebration, when they realized the Cup had been sitting outside unsupervised — under a tent on their front lawn — for quite a while.

“Guess we should go check to see if it’s still there,” Jay said to his father.

Luckily, it hadn’t moved.

During his time with the Cup, Jay came to see the magic of the trophy and the mesmerizing effect it had on everyone who came close to it.

When players brought it to a retirement home, seniors approached it and would point out a name of someone they used to know or watch on TV who played hockey, Jay said.

It towered menacingly over children in a preschool class, but they gawked excitedly at it, already aware of the trophy’s cultural significance, he said.

It was a riveting time for Jay as well, but there’s one thing he wanted to make clear about being part of such a sacred tradition.

“The excitement, the parade, a million and a half people yelling and screaming your name down Broadway — it was a real rush,” he said.

“But let’s keep it in perspective: that was just one day in one year of a person’s life,” Jay said.

“There’s been so many times I’ve been blessed: with a good wife, with three healthy kids, with my health — there’s a lot of things to be thankful for,” he said.

“And this was just one of many.”

Kitchener Citizen

February 13, 2019

Jay Wells and his brother, Bill, came very close to shutting down an entire border crossing between the U.S. and Canada in the summer of 1994.

“Do you have anything to declare?” A Canadian customs officer asked Bill, through the rolled down window of their car.

“Well, if the Stanley Cup is something we have to declare, then yes, we have the cup in the backseat,” he replied.

The officer instructed them to promptly pull over and remove their precious cargo for inspection.

Four out of five of the customs booths on the Lewiston-Queenston Bridge suddenly closed, and all but one of the border guards had vanished from their posts.

“The cars were all honking and they all had to get into one line … and the customs officers, all they wanted to do was get their photo with the Stanley Cup,” Jay said.

“I feel bad for the one guy who had to stay.”

Now, for the 25th anniversary of his Stanley Cup win with the New York Rangers, Jay and his family travelled south February 8 to reunite with his old teammates.

Before leaving, Jay said he was looking forward to reminiscing with the old gang, and sharing the celebration with his wife Colleen and three daughters.

“It’ll be a good opportunity for them to get a taste of what life was like back in my glory days,” Jay said.

But he remembers two incidents in his childhood that could have kept him from getting on the ice at all.

At age one, he was scalded with hot water and lost a large section of skin, and a year later he broke his arm and multiple ribs after getting caught in a tractor’s power take-off shaft.

Luckily, his recovery was swift and he was eventually able to lace up his skates, pick up a stick, and join his older siblings on the frozen pond behind their farmhouse west of Paris.

“I learned an awful lot from my older brothers. I would try to do things that I saw them do and that helped me to develop into the player that I became,” Jay said.

The NHL first recruited Jay’s older brother, Bill, to train and play for the Montreal Canadiens.

He trained with Montreal for two years, but never made it onto the team’s official roster, eventually being sent home.

“If I went to the Montreal Canadiens — with how strong they were back in the ‘70s — I probably would’ve never made the NHL,” Jay said.

The Los Angeles Kings, an up-and-coming team at the time, drafted Jay when he least expected it.

He never intended to play professionally.

And after he’d honed his skills on the ice with the Kings, he eventually found himself signed to the New York Rangers alongside an all star team.

Be that as it may, the good news came with a catch, or rather, a curse.

There was an entrenched rivalry between the Rangers and the New York Americans, who played in the NHL between 1925 and ’42. Both teams called Madison Square Garden their home rink, but their landlord also owned the Rangers.

Many theories have circulated about the cause of the Curse of 1940, also known as Dutton’s Curse, including one Jay remembers being told before a game against the New York Islanders.

Legend has it that after the Rangers won the Stanley Cup in 1940, high on their victory, they forced the Americans team out of the arena they shared, bluntly gesturing to “find somewhere else to play,” Jay explained.

The owner of the evicted team, coach Red Dutton, placed the long-lasting curse on the Rangers, stating they would never win a Stanley Cup ever again.

New York Islanders fans would ominously chant “1940” repeatedly against Jay and the Rangers whenever the teams met for a game.

The curse was finally lifted in the first round of the playoffs that would lead to the Rangers’ ultimate success in 1994.

Mark Messier, a five-time Stanley Cup champion who played alongside Jay, gave the Rangers a succinct piece of advice for winning the trophy: “If you can’t see it, you’ll never seize it.”

There was certainly a lot of pressure on them to win from their defiant coach, Mike Keenan, who only stayed with the team for one year and departed after their victory.

Keenan was a motivator with an attribute that was unique, Jay said.

“He knew how far he could push a person to get the most out of them,” he said.

And everyone on the team needed to be pushed, “they couldn’t be complacent,” Jay said.

As the Rangers made their way through the playoffs and into the Stanley Cup Finals, Jay realized playing well wasn’t just about maintaining his talents on the ice.

“As much as it is physical, it’s twice as much mental,” because if you internalize your wins or your losses too much, you can let your guard down, he said.

The Rangers beat the Vancouver Canucks in game seven of the finals, with team captain Messier scoring the game-winning goal.

However, the moment the win fully sank in for Jay was a while after the final game. It hit when he returned home to Paris.

He and his father were drinking coffee after a small family celebration, when they realized the Cup had been sitting outside unsupervised — under a tent on their front lawn — for quite a while.

“Guess we should go check to see if it’s still there,” Jay said to his father.

Luckily, it hadn’t moved.

During his time with the Cup, Jay came to see the magic of the trophy and the mesmerizing effect it had on everyone who came close to it.

When players brought it to a retirement home, seniors approached it and would point out a name of someone they used to know or watch on TV who played hockey, Jay said.

It towered menacingly over children in a preschool class, but they gawked excitedly at it, already aware of the trophy’s cultural significance, he said.

It was a riveting time for Jay as well, but there’s one thing he wanted to make clear about being part of such a sacred tradition.

“The excitement, the parade, a million and a half people yelling and screaming your name down Broadway — it was a real rush,” he said.

“But let’s keep it in perspective: that was just one day in one year of a person’s life,” Jay said.

“There’s been so many times I’ve been blessed: with a good wife, with three healthy kids, with my health — there’s a lot of things to be thankful for,” he said.

“And this was just one of many.”